Given the last election, I figure it’s a good idea to take stock of how marginalized people have traditionally survived in times of . . . strife.

Although not exhaustive, this could be a good place to start if you’re looking for some help. I focus on three groups:

People who may lose their reproductive rights.

People who may lose their rights for being queer.

People who may lose their rights for being an immigrant, and People who may lose their rights for being perceived to be an immigrant.

It’s useful to remember that, for much of American history, people in those groups have been existing and fighting regardless of what party is in the White House. It can be easy to forget that a Democratic President doesn’t mean protections for marginalized groups—see our post on queer rights in Ohio—as states like Ohio will still oppress Queer, Black, and Brown Americans—see our other post.

Black Americans are unique in that they’ve been targeted since before this country was a country. Nevertheless, this post will focus on the 3 groups above as they’ve been expressly called out by the new administration as targets of their ire.

1. Reproductive Rights

There are few issues more pressing for Ohioans than the right for people to control their own bodies. Ohioans passed a constitutional amendment enshrining that right for all time—right? Maybe, but maybe not.

The Ohio General Assembly despises Ohioans’ making their voices heard, and state politicians aren’t afraid to say it outright. These freaks don’t care about democracy, the outcomes of a fair election, or dutifully representing the people of Ohio, and for that reason, reproductive rights remain an issue.

So wadduwe do about it? Well, first and foremost, there is the Abortion Fund of Ohio, which is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization (meaning they don’t exist to make a profit, have a charitable purpose, and can accept tax-exempt donations). The AFO works to connect people who need support to receive an abortion with the funding or other resources they need. Check out their website for more.

But what we’re facing could get much worse than we’ve seen in recent history, where reproductive rights and access to women’s healthcare could just cease to exist. Well, they say history can often tell us the future—so what’s worked in the past?

Buckle up, because this ain’t a curriculum-approved history lesson.

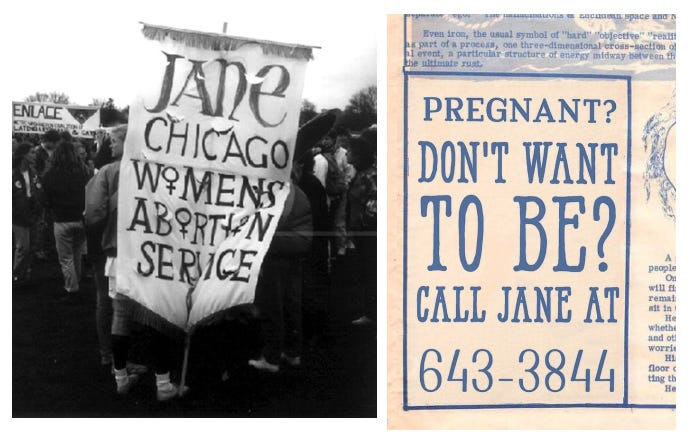

As always, people got loud—but sometimes moving in silence can be just as useful. In Chicago, there was a particularly successful group called the Jane Collective who ran an underground abortion service. There’s a wonderful Your Wrong About podcast episode which goes into amazing detail about them, but here’s the 10,000 ft view.

The year is 1969 (nice), abortion is illegal in Illinois(not nice), and although I like to pretend it isn’t, Chicago is inside Illinois. So, women there organized a hotline where anyone could call to access an abortion.

God bless the technology at the time. The group was able to put out cards, ads, and flyers with the phone number and have conversations with the people who called in.

Through those conversations, Jane Operatives would determine whether or not the caller was A. a cop, B. in need of an abortion, or C. in need of some other form of reproductive care. The callers’ information was written on note cards and the Jane Collective discussed whether or not to take steps. If they decided to proceed with an abortion, they picked up the caller, drove them to the location—doubling back, driving in circles, and making quick turns to avoid being followed by the fuzz.

After sufficient anti-following provisions were taken, Operatives would go to an apartment where a doctor—or someone who knew how to perform an abortion—would do the procedure. Of course, there were issues. Without the Jane Collective, finding someone who’d perform an abortion was difficult and expensive, and there were plenty of shithead doctors who would extort, assault, or otherwise abuse the power they had over the women. The Collective combated this by finding the “good ones” who could be trusted and turned to them for help.

Now, none of this is to say abortions were free, because they weren’t. Although some sawbones were passionate about abortion, they still needed to be payment for the risk they were taking. The Jane Collective leveraged their connections to raise funds, lobby the doctors for lower prices, and even learned how to perform abortions amongst themselves.

And if the cops got wise, there were options.

The first ripcord was playing the old “oh! I didn’t know! I’m just a woman!” trick. If caught, Collective members would ditch or eat the contact cards and then just play stupid, which the cops believed because sexism. The Collective used the technology of the time but relied on paper notes which could be destroyed. Especially in today’s day and age, phones and tech are just as much of a benefit as a drawback. Tech companies have clearly taken the side of right-wing psychos, and all the data they collect will be used against you—location, what devices you’re near, call records, etc.

Eventually, their luck eventually ran out, and cops busted one of their apartments. Luckily, the Collective were able to delay their case until Roe v. Wade was decided, and the case was dismissed.

It’s vital to understand that the women who organized the Collective were not just any women either. These were the daughters of cops, judges, lawyers, and politicians, and were h’white, whereas a lot of the callers who needed help were poor and women of color. As with all things, the rich are exempt; they’re able to pay to travel to another state—or another country—and have connections to people who can help them. This is what using privilege looks like in action.

2. Queer People

Queer people have been around forever, and they’ll still be here tomorrow. In the United States, our history of Protestant Christianity includes regressive anti-sodomy and “decency” laws. Even worse—as we wrote before—in Ohio, there are no protections for queer Ohioans, and gay marriage is illegal under state law.

What is especially salient is that there are no protections for trans Ohioans, in light of the two pieces of legislature recently signed into law.

Rough look.

But it’s not like anything has changed. Ohio’s government has been ambivalent towards queer people at best until now.

According to lgbtqcenters.org, there are quite a few LGBTQ centers north of Dayton. The website also lists what type of services they offer as well as contact information and operating hours. Centers like these can actually help direct people to resources, and a cursory glance at the literature shows significant improvements to the mental health, self-esteem, and prevention of substance abuse for the people who visit.

As you can see, the vast majority of centers are around the Big 8, but herein lies a problem. It’s great that the cities are serviced, especially as many cities have higher rates of poverty than rural areas to meet potential needs, which is a trend that’s fairly unique to the State of Ohio. That being said, Ohio has an evenly distributed population in terms of geography, so there are many areas which lack any place for queer people—especially young people—to turn to.

But there are still internet resources. To list a couple, the Trevor Project was founded specifically for trans youth, but also has resources for anyone in The Community to find friends, mental health assistance, and general life advice. Everywhere is Queer is an app that lists different businesses that are either queer-owned or queer friendly. It seems that businesses are volunteering themselves to be on the list, so take that for whatever it’s worth. Finally, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Discrimination has a good list of resources on their website as well. Obviously this isn’t an exhaustive list, but searching “queer resources” online will yield a lot of results.

Ultimately, I have no clue how far the administration will go. I doubt it will go as far as internet restrictions, but who knows. If that happens, it’s important to remember that queer people have been finding community with each other since before there were centers, before there were websites, before it all.

In the past 20 years, young people have become more and more comfortable identifying as queer, but the youngest members of the community didn’t experience the government’s ire during the aids epidemic, nor the lavender scare, or any governmental persecution. I’m far from a boomer myself, but it’s important to know history—what’s been done—because it often charts the course of what will come.

Interview with Noelle Richard

To weigh in, I spoke with a Queer New Orleans Artist, Noelle Richard. I thought of them because New Orleans (as you’ll see) has a unique relationship with governmental support and forming community.

The sentiment of distrust is borne out of abundant and unrelenting proof in action that the government doesn't care if the people of New Orleans live or die.

JP: To me, living in New Orleans, where governmental trust seems to be one of the lowest in the country, can teach useful lessons about living, not against the law, but outside of the law. Do you see any parallels?

Noelle: Yes I agree both those things are true here.

JP: Since you live there, can you tell me what the general sentiment towards the federal and state government is?

Noelle: In my experience, people in New Orleans have little to no trust in the government, at any level. As a historically 'blue' city, New Orleanians have often been punished by the state government, a la "we're going to teach those liberals a lesson." The most obvious example of this is post-Katrina, when the federal government allotted relief dollars to the state, and state leaders did not direct that aid proportionately to the city. Kanye famously expressed the sentiment here when he said on live TV just days after Katrina, "George Bush doesn't care about Black people." However, there are innumerable answers to your question, which as a relatively recent and white transplant I am still catching up on. The residents of Gordon Plaza, a development of homes on top of a toxic landfill and marketed specifically to Black families, have been engaged in a decades-long battle with the local government for a fully funded relocation. Most recently of course, we watched the state governor go on national television to reassure people that it was "just locals" who were killed on Bourbon Street on January 1st 2025, and that tourists should still feel safe. This isn't even getting into the details of the gross deregulation of the city's sole energy provider, Entergy (which has directly caused numerous resident deaths), the nonexistent infrastructure (instagram.com/lookatthisfuckinstreet), or rampant prioritization of tourism over the daily lives of the people who make up the culture and the workforce which brings the tourism in! The sentiment of distrust is borne out of abundant and unrelenting proof in action that the government doesn't care if the people of New Orleans live or die.

JP: You’re also apart of the of the queer community—and when I say that I think many people envision some large meeting that all queer people go to—what does your queer community actually look like?

Noelle: I don't know that that phrasing makes a ton of sense for me honestly; it's not as though I have an explicitly queer community separate from everything else (emphasis added by JP). I want to be in relationships that don't require me to explain/defend my gender/sexuality to them; this means usually, I'm around other queer people. I try to surround myself with other people finding their ways through life outside of typical paths or cultural expectations.

JP: It seems that many liberals believe that the queer community lives and dies by whether the government is “friendly” (meaning the government want to either moderately expand, or not change queer medical access and personal rights) or “unfriendly” (meaning the government wants to take away queer rights and criminalize queer existence). What’s the reality?

Noelle: If there's anything evident from LGBTQ history, it's that the government's acceptance or friendliness toward queer people is fickle at best. The politics of a region are only one part of why someone might live there, if they have the privilege to move freely between locations at all. Queer people have been and will continue to be everywhere. The belief in question to me sounds like saying that all cis women should leave states that have restrictive reproductive health access. It's just not going to get into a deep or interesting conversation.

JP: What does it look like to truly rely on other queer people, and allies to some extent, as opposed to looking to governmental organizations for help and protection?

Noelle: I think we're doing it already. Trans people have always and still are giving each other drugs since the "correct" channels haven't always existed and still are incredibly unreliable. Warning each other about doctors, bureaucrats, chasers, who make our lives more difficult. It's already happening all the time constantly. Who's covering the cost most of the surgeries and emergencies among queer people? (hint: it's not our workplaces or insurance companies)

End.

I think Noelle’s perspective highlights a few key issues.

1. The Queer community isn’t an organization. It isn’t a PAC, it isn’t a non-profit, it isn’t a club. To use a cliche, home is where the heart is.

Queer community is you and your friends. It’s wherever you feel safe. It could be online where one friend uses your preferred pronouns, or maybe a D&D game where you get to play as a gay orc man.

2. Being outside the law isn’t the same as being against the law. Let me be explicit, the Northeast Ohio Left PAC does not endorse breaking the law. Being outside the law, in the grey space where politicians pretend you don’t exist—that is a space where queer people may return to. Remind yourself that the government isn’t your friend, laws don’t determine what is morally right and wrong, and politicians aren’t celebrities. New Orleans is a prime example of how an entire city can be thrown by the wayside, but the people there will still persist.

3. To find and build your community, you may need to go outside and meet people. I say this as a terminally online introvert myself, but reading about The Jane Collective, about underground queer space, there are times we all need to go outside. There’s a scene in Mad Max: Fury Road —a film which has a lot to say on the direction we’re going—that I think lines up nicely with a final quote from Noelle.

“The politics of a region are only one part of why someone might live there, if they have the privilege to move freely between locations at all. Queer people have been and will continue to be everywhere. The belief in question to me sounds like saying that all cis women should leave states that have restrictive reproductive health access. It's just not going to get into a deep or interesting conversation.”

3. Immigrants

Both on the federal and state levels, Ohio has been a hotbed of anti-immigrant sentiment. Must be something in the water. Other than lead.

During Trump’s first term, there were two huge raids on ohio worksites that detained and deported close to 300 migrant workers. Our bloodthirsty politicians sang praises for that action, clearly not giving a shit about people in Ohio unless they’re rich and white. And more recently, Haitian migrants are being targeted in Springfield for racist lies, with Trump threatening their status directly as top of his Brown-person hit-list.

But this is far from the first time the government has mistreated immigrants and Brown people in general.

First and foremost, there was a court case not too long ago that spurred a lot of fear. The above image was circulated online, and off the cuff, it does seem very scary. Looking into the issue, the ACLU published several great pieces, one of which details what really changes with this “100-mile” zone.

TL;DR, there are two changes.

Checkpoints are legal in these zones.

Within 25 miles, some cops can enter private property—but not dwellings—without a warrant. While this may seem better than what people called this zone initially—a constitution “free” zone—I think it could just be that simple. Checkpoints set up down Euclid ave, armed goons asking to see our papers, etc.

But again, we’ve been here.

Japanese Americans were concentrated into camps during WW2, and present-day immigrants are separated from their families and held in camps along the southern border. As with everything in the United States, the issue is always connected to slavery or 9/11—and sometimes both. ICE was formed in the panic after the twin towers fell, taking advantage of the confusion and blood lust to swap from naturalizing people who crossed the border illegally to hunting them like animals.

The Ohio Immigrant Alliance is a non-profit dedicated to supporting immigrants in Ohio, advocating for the dignity and rights of anyone who chooses to make Ohio their home. They have a number of sub-groups working on projects building grassroots organizations, helping with legal fees and connecting those in need with attorneys, and lobbying legislatures to change the laws on the books.

CRIS is another organization that helps immigrants, specifically in Central Ohio. In truth, there are a myriad of organizations that help advocate for the betterment of immigrants in Ohio, but we’re going into, and may have never really left, a dark time.

“Immigrant” is not a term that will be used in a positive way. It will be used to “other” a group, a group that is now them, the outsiders, the problem, the enemy. Three immigrants walk down a road. A guy from Finland, a guy from Syria, and a guy from Mexico. Which two do you think are getting asked for their papers?

The future will be a litmus test for whiteness, who’s pale enough to pass under the cop’s gaze without drawing attention? and more importantly, who’s not? This will be a time where they try to get you to turn in your neighbors.

Like I said above, the history of immigrants in the United States and Ohio is tied with slavery and post-9/11 racism. Birthright citizenship only started because Congress needed a way to protect formerly enslaved Americans, and the bill that established it—the Civil Rights Act of 1866—was even vetoed by Andrew “Jerk-off” Jackson because he didn’t believe Black people were equal to whites. His veto was over-ridden, but I think the message is clear.

Even when some parts of the government have sympathies for people of color, there’s always been a loud and powerful voice against them.

Flash forward a mere 60 years, and for the first time in American history, the government decided to limit the amount of immigrants allowed into the country based on . . . drum roll please . . . eugenics and fear of radicalism! Using the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, our government started us down this long hill of shit.

Pew did a study investigating who’s here, why they’re here, and who they live with if you’re interested—but that’s not what this is about. The Migration Policy Institute also has a history of immigration law in the United States, which you should check out. But obviously lacking is a cute “how to find your local undocumented friend!” section.

Without anything wild happening, just assume standard rules apply. Don’t talk to cops, don’t talk to ICE, and if someone needs help, help them. As with queer communities, it isn’t as if there’s a place you can find of undocumented immigrants—well, outside of modern slavery. It’s the communities you create.

Anonymous Interview

But I’m not an immigrant. So I talked to a someone (who asked to remain anonymous) about their experience.

I genuinely don’t see any significant differences between being a part of the LGBTQ community overseas and being a part of it in the U.S., even considering the legal “safeguards” the U.S. has in place for us. For a lot of us, there’s always a sense of apprehension with being out or even closeted.

JP: You took a lot of trips as you were growing up traveling between Lebanon and the US. Was there any significant difference between how Lebanon felt about queer people, and how the US felt as a child?

Anon: Compared to the U.S., there weren’t any LGBTQ-based discussions that I was aware of in Lebanon, at least not ones that I was exposed to as an adolescent and child. Even in the U.S., it really wasn’t until middle school that I was exposed to discussions surrounding the LGBTQ community. And even then, like most people, those discussions were confined to friends, certain spaces, and in rare instances, by teachers who were willing to make space for it in their classrooms.

JP: How about now, looking back?

Anon: I firmly believe that there were pockets of LGBTQ support systems overseas, but for obvious reasons, these spaces were limited to specific members and individuals and were never openly discussed outside those spaces. But I genuinely don’t see any significant differences between being a part of the LGBTQ community overseas and being a part of it in the U.S., even considering the legal “safeguards” the U.S. has in place for us. For a lot of us, there’s always a sense of apprehension with being out or even closeted.

JP: What's your relationship with the word "immigrant"?

Anon: When I first moved here, it felt derogatory because “immigrant” was used by classmates, parents, and strangers to other non-white individuals. That connotation, however, went away with age and time. Peers became accepting, hatred was ignored, and you become more familiar with which spaces to affiliate and be comfortable with.

JP: Is it an identity you strongly identify with? Why/Why not?

Anon: Absolutely. Growing up makes you realize the gravity of erasing something as prominent and as defining as being an immigrant. In some contexts, non-affiliation, to me, is equal to erasure. I quickly understood that refusing to affiliate or identify with my immigrant background would be to reject and erase parts of my life, childhood, memories, and my ethnicity; in other words, reject and erase the foundation of my existence.

JP: What are you thinking about as the next administration, Ohio and Federal, comes into office, and how does it affect how you seek community?

Anon: It’s safe to say that the majority, whether allies, community members, or people as a whole, are nervous about the prejudice, setbacks, and overall stain that this administration will have on vulnerable and underrepresented communities. Now more than ever, many have begun intentionally seeking community to support themselves and loved ones.

JP: Do you, and if you do how do you, find support and community with other immigrants? Is it important that they are the same ethnicity as you?

Anon: Immigration, specifically immigration tied to safety/health concerns, is an experience that many will not understand nor relate to unless they experience it. A lot of immigrants find comfort by finding others who can relate to this experience, but I’m confident in saying that most of us are not greedy with finding specific experiences or backgrounds in people in order to relate to. To go further, the common denominator for most immigrant communities is wanting a better life for themselves and their loved ones, to escape some degree of institutional oppression. That said, there’s always something, if not that common denominator, that tethers immigrants to other immigrants.

JP: I think when a lot of people hear "the queer/immigrant community" they think of a giant meeting where all queers or immigrants meet. What does the queer community actually look like to you? What does the immigrant actually community look like to you?

Anon: It’s not uncommon for queer and immigrant communities to hold larger events or “conventions” for both the public and the greater, macro-level queer/immigrant community. But to many, a “community” simply means the access to support: It’s having the ability to reach out to others for support and doesn’t necessarily require a material aspect or a physical space to be held. “Community” manifests through outreach, whether a phone call, a text, or taking a walk outside with your friends. It’s a mode of resistance that involves existing with and supporting others in the face of limitations, prejudice, and hardships.

to many, a “community” simply means the access to support: It’s having the ability to reach out to others for support and doesn’t necessarily require a material aspect or a physical space to be held. “Community” manifests through outreach, whether a phone call, a text, or taking a walk outside with your friends. It’s a mode of resistance that involves existing with and supporting others in the face of limitations, prejudice, and hardships.

Subscribe now for Ohio hot takes from the left. Visit our website for more info at neoleft.org. Keep up with our social media antics on Twitter and TikTok.